Does Dynamic Pricing Hurt Customers?

If you’ve ever used a ride hailing app, chances are that at some point you’ve experienced a higher than expected fee. Surge pricing is surely unpleasant when you’re on the paying end; almost everyone would prefer to pay less than more for a given product or service. Yet, as a form of dynamic pricing, such adjustments seek to balance the supply of drivers and the demand of riders, ensuring a well-functioning marketplace.

This functionality is core to market leaders such as Lyft and Uber. But does it have to be?

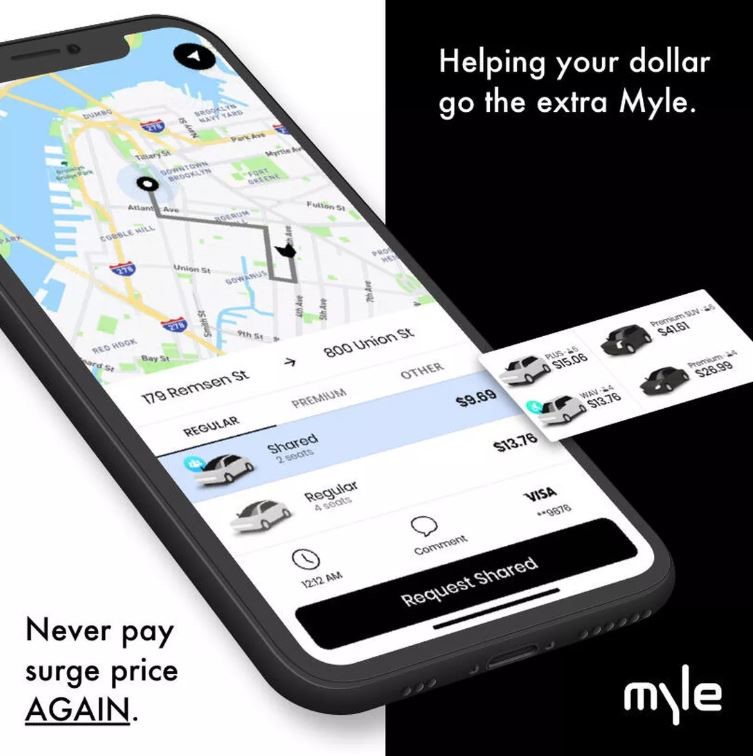

That’s the question being asked by Myle, a new ride hailing app recently launched in New York City. As CNET Roadshow reports, “Myle’s claim to fame is the promise of zero hidden fees and absolutely no surge pricing.”

Myle hopes to solve multiple problems at once:

- It eschews any form of surge pricing,

- It promises to have zero hidden fees, and

- It expects to charge riders an average of 10% less than rivals.

This is a fascinating story to explore through the lens of pricing strategy. As we’ll see, there are only two options:

- Myle is dead upon arrival, or

- Lyft and Uber’s dynamic pricing is seriously broken.

Which is the right scenario? A foundational understanding of pricing and business strategy suggests the answer.

Let’s dig into Myle’s three claims.

The Purpose of Dynamic Pricing

In Myle’s telling, dynamic pricing (surge pricing) serves only to fleece the rider. Higher prices are simply captured as more revenue by the driver and/or ride hailing company, and riders would be better off without such surges. The pie is fixed, and riders deserve a bigger share.

However, understanding the principles of dynamic pricing reveals a different story. From this perspective, higher prices reflect an increase in demand. The purpose of those prices is both to encourage more drivers to become active and to encourage riders to consider alternatives.

The result is a better functioning marketplace that balances supply and demand, limiting shortages in driver supply. Too small a supply causes long rider wait times and eventually fewer people using the service. In this story, dynamic pricing helps to grow the pie and adds value to both drivers and riders.

By rejecting dynamic pricing, Myle is essentially rejecting the latter story. They plan on doing what Lyft and Uber never could: being able to match supply, demand, and wait times without the help of the pricing mechanism.

Fees and More Fees

As for hidden fees, it’s not clear which fees Myle is referring to. True, Uber used not to provide the final price of a ride, instead showing how the fare would be calculated. I call this pricing transparency, and this level of transparency was no different than a taxi’s. However, as of 2016, Uber had already shifted its model to one of price transparency, clearly showing the final fare before the ride is booked.

Perhaps Myle is referring to cancellation fees, which are still applied sometimes when a rider cancels a ride that is on its way. Myle promises not to have such fees. However, there is a reason these fees exist. Cancelling a ride is harmful to the driver who has wasted time and mileage going toward a rider. And it’s harmful to the app ecosystem by tying up resources.

Having a small cancellation fee is a way to shape customer behavior: if their activities are costly, they should assume some of that cost. Having a cancellation fee makes Lyft and Uber’s platforms better at matching.

By rejecting cancellation fees, Myle risks the stability of its matching. This sounds like a broken platform. But we’re not done yet.

Price Warriors

According to Engadget, Myle also “hopes to differentiate itself by giving people a more affordable alternative to Uber and Lyft”. But it is hard to see how Myle can undercut these competitors enough to make up for a worse experience. Uber and Lyft are already competitively priced to taxis, if not cheaper.

They are also not afraid to forgo profits to keep prices low. Uber is on the precipice of profitability already, and unless Myle can also count on SoftBank as an investor, it’s hard to see how they could hope to win a price war against better-funded marketplace leaders. Who can afford to stay unprofitable longer?

Conclusion

At this point, we can see that Myle is attempting quite the feat. It promises to have no surge pricing, no cancellation fees, and lower rider fees. We can see that all three of these have the effect of discouraging drivers, increasing rider wait time, therefore discouraging riders and creating a vicious negative feedback cycle. Its promises of transparency and lower prices are either undifferentiated or actively harming the platform it seeks to create.

Unless the dynamic pricing mechanism behind Lyft and Uber is seriously broken, it appears that Myle is not only bringing a knife to a gunfight but is also holding its knife by the blade.

Myle unfortunately looks to be a cautionary tale, illustrating the importance of understanding how pricing and business strategy must work together, especially in a two-sided market, to create value for both sides.

Dynamic pricing and the occasional cancellation fee actually make Lyft and Uber better platforms and therefore more useful to both riders and drivers.

“You come at the king, you best not miss.” – Omar Little, The Wire

For more on price vs. pricing transparency, dynamic pricing, two-sided markets, and more, check out my Amazon bestseller The New Invisible Hand: Five Revolutions in the Digital Economy.

Tagged: Amazon, business strategy, dynamic pricing, Lyft, Myle, pricing transparency